Forged in Blood II, the final novel in the Emperor’s Edge storyline, is now out at Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Smashwords, Kobo, and Apple.

Since I already included the first part of Chapter 1 at the end of FiB1, I guess I better do two preview chapters here. I hope you enjoy the sneak peek. Thanks for reading!

Forged in Blood II: Chapter 1

Amaranthe wasn’t dead. At least, she didn’t think so. Dead people probably didn’t hurt all over. The flying lifeboat had insulated them from the crash somehow, though her head had connected with a couple more walls before the craft stopped bouncing.

“Books?” she asked into the darkness. “Akstyr? I hope one of you is alive, because I have no idea how to open that door and get out of this thing.”

A deep, pained sigh came from underneath her—she’d tumbled back on top of the men again during the landing. Amaranthe crawled to the side, though there wasn’t much open space in the cramped cabin.

“One of you?” Books repeated. “You have no preference as to whom your survivor is, nor a belief that one of us would be more equal to the task of opening a door secured by ancient unfathomable technology, or of deciphering instructions written in an inscrutable alien tongue?”

He must not be wounded horribly if he could utter all that.

“You saw instructions?” Amaranthe asked.

“Well, no, but it was hard to get a good look in the dark. And while we were being shot at.”

“We still have the darkness problem,” Amaranthe pointed out. The viewport that had appeared while they were in flight had disappeared before the crash, leaving the inside of their lifeboat utterly black. “Akstyr?” Amaranthe patted about, finding his back, then following it up to his neck so she could check his pulse. She hadn’t heard from him since he’d hurled himself into the craft, dodging the incendiary beams of those indestructible cubes.

He mumbled something at her touch on his neck.

“What?” Amaranthe breathed a sigh of relief. They might be a thousand miles from the capital, but at least they were all alive.

“Wanna rest,” he slurred. He lay facedown, his mouth pressed into the floor. “But some muddy’s knee is up my buss.”

“I think he’s referring to your body part,” Amaranthe told Books mildly, fairly certain she wasn’t sitting on anyone anymore. Though she couldn’t be sure what a “buss” was.

“Ah.” Books shifted. “I’d wondered why that section of the floor was so bony.”

“Ma buss not bony,” Akstyr slurred.

Maybe more than his positioning accounted for the mangled words. Amaranthe prodded his scalp and found a lump. He must have hit his head, among other things. He’d also been wearier than a long-distance runner after a race when he’d stumbled into the lifeboat. Out of curiosity, Amaranthe investigated her own scalp. She snorted when she found three lumps. Maybe her words were coming out slurred too.

Books groaned as he stood up. “I’ll see if I can find the—”

The door slid up, the material disappearing into the hull. Starlight, freezing air, and the scent of snow-covered pine trees entered. The cold air slithered through Amaranthe’s leggings, and she tugged her dress down as far as it would go. A chunk of blonde hair tumbled into her eyes. She shoved it behind her ear and wished for a beaver fur hat. She had a feeling her Suan costume wasn’t going to be suitable for this next adventure. Not to mention that ridiculous underwear she’d let Maldynado pick out. One slip down an icy slope, and she’d have snow all the way up her—

She sighed. At least the fur boots were practical.

“Good work, Books.” Amaranthe patted around, finding two of their rifles. The cartridge ammunition littered the floor, and she scooped up as much as she could. Who knew what they’d face out there? The craft could have plopped them down into grimbal or makarovi territory.

“Uhm, yes. Except I didn’t do anything. Perhaps it sensed that we’ve landed and is ready to spew us forth into the world of its own accord.”

“That’s fine,” Amaranthe said. “I’m ready to be spewed.”

“Think I was already spewed,” Akstyr muttered and curled his legs up to his chest. “It’s cold. I wanna stay here and sleep. Be warm.”

“If the door closes again,” Books said, “you may be stuck inside forever, because I don’t know how to open it.”

Akstyr lurched to his feet and stumbled out into the snow. “Never mind. I’m ready.”

He barely made it through the threshold before slumping against the hull.

“Why don’t you stay here,” Amaranthe suggested, “and try to make a fire? Books and I will figure out where we are.”

When she stepped outside, shivering at the wind scouring the mountainside, her optimism floundered. A few pines, the bases half buried by drifts, dotted the slope below them. They’d landed above the tree line and, she feared, far from any towns. Not good. They weren’t prepared for winter wilderness survival conditions.

Books stepped out beside her and surveyed their dark surroundings. “Hm.”

“Does that mean you don’t know where we are either?” Amaranthe wished she had an idea of how far they’d flown and in which direction. Were they fifty miles from the capital? Or five hundred? Though she’d been out of Stumps more times in the last year than in her entire life prior to meeting Sicarius and the others, she didn’t exactly qualify as a world explorer yet.

“That may be a pass over there,” Books mused. “And those four peaks in a row remind me of the Scarlet Sisters, though there are arrangements like that in other mountain ranges, too, I’m certain. We don’t seem to have left the climate zone, albeit we’re at a higher and, ah, chillier altitude. The stars are familiar.”

“That was a yes, right? You don’t know where we are?”

Books grumped something that might have been agreement.

“I hear a train,” Akstyr said from where he still leaned against the lifeboat hull, his eyes closed, his arms wrapped tightly about himself and the rumpled guard uniform he’d acquired on the way down to the Behemoth.

Amaranthe perked up. He was right. She caught the distant chuffing of an engine working hard to pull its load up an incline.

“Oh!” Books said. “Those are the Scarlet Sisters then. That’ll be the East-West Line, and that train is either traveling to or from Stumps.”

Given the chaos the Behemoth’s appearance must have caused—Amaranthe had no idea if it’d sunken back down into the lake or taken off for some distant destination, but people would have witnessed it either way—she thought traveling from was the more likely scenario. Or fleeing from perhaps. Still… “Let’s see if we can get to the rails before it’s gone. If it’s going to the city—”

“It could be our ride home,” Books finished.

“Does this mean no fire?” Akstyr asked.

“Sorry.” Amaranthe grabbed his arm. They’d have to hurry to have any chance of scrambling down the mountain in time.

“You can sleep on the way back to the city,” Books said. “We’re over one hundred and fifty miles from Stumps.”

Amaranthe’s mind boggled at the idea that they’d traveled that far in a couple of minutes, but she was more concerned about getting back now. She handed Books the other rifle and led the way down the mountainside, plowing through snow that enveloped her legs up to her knees with every step. It didn’t take long for sweat to break out on her brow and weariness to slow her limbs. Her newly acquired bruises and lumps further protested this unasked-for workout, and she wasn’t altogether upset when Akstyr announced he was too tired to go on. They stopped to rest, huddling beneath the boughs of a tree for protection from the wind. The chugs of the train faded from hearing.

“I believe that one was heading away from the capital,” Books said.

Amaranthe doubted he could tell—with the mountain walls, canyons, and crevasses distorting sound, she couldn’t—but she could understand the desire for optimism. Especially when her toes were freezing in her boots. Once again, she was glad she’d ignored Maldynado’s suggestion to wear sandals to the yacht club.

“Anyone have any food?” Akstyr asked when they started out again.

“Not unless Amaranthe’s purse contains more than glue for her fake nose,” Books said.

“Actually, I have some of Sicarius’s dried meat-and-fat bars in here,” Amaranthe said.

“I’d rather eat the nose glue,” Akstyr said.

“You may change your mind after another day out here.”

Akstyr’s grumbled response was too low to make out.

They continued their trudge, cold and miserable and unequipped for the terrain, though traveling downhill took some of the anguish out of the trek. As dawn broke over the mountains, the clear sky untouched by smog and impressive in its gradated pinks and oranges, they reached the pass. The cleared tracks, snow piled high to either side, wound through the treacherous terrain, a black snake navigating boulders and slopes.

Amaranthe angled toward a bridge, the support structure towering well over the tracks. It’d be an opportune place—or rather the only place—to jump onto a moving train, and the team had practiced such maneuvers before.

That didn’t keep Books from groaning as they approached. “Why am I certain of what’s in your mind and certain it’ll be dangerous?”

“Really, Books, we’ve been chased by man-incinerating machines, flung from an aircraft so alien our science can’t begin to fathom it, and hurtled hundreds of miles to crash on a mountainside. You’re going to complain about something as benign as hopping onto a train?”

“She’s got a point, you know,” Akstyr said. “It’s freezing out here. I’d do just about anything to get off this mountain.”

Books’s harrumphed.

Amaranthe nudged Akstyr. “He’s just complaining out of habit now. It’s what men do when they get old.”

“I am not old,” Books said. “I probably wouldn’t even have any gray hair yet if I weren’t traipsing around after you all the time. This last year has been enough to age a man ten.”

“That’s a lie. You had gray temples when I met you.”

“Fine, these last two years have been enough to age a man ten.”

They’d reached the base of the bridge, frothy white water frozen into ridges of ice far below, and Amaranthe stopped teasing Books. She didn’t wish to remind him of the death of his son and the difficult times he’d faced before joining her team. Granted, he was right that the last year hadn’t been without difficulties either. But it’d all end soon. One way or another.

This time, Amaranthe heard the train first, the distant chugs coming from the west. “It’s heading to the capital. This is our opportunity.” She waved for them to climb halfway up one of the towers rising from the suspension bridge. “It’s still dark enough that, if we’re lucky, the engineer won’t notice us crouching up there.”

“We’re due some luck,” Books said.

“Let’s be happy there are trains coming through and that we didn’t have to wait for days out here.” The East-West Line was a busy one, taking passengers and freight from Stumps to the various ports on the west coast and back, but Amaranthe hadn’t known what to expect with the capital locked down. She did know the train would be stopped and searched before being allowed into the city. Best to worry about getting on first. “Akstyr, can you make the climb?” she asked.

Books was shimmying up the steel supports, but Akstyr stood at the base, staring upward, his eyes sunken and his body slumped.

“Yes,” he sighed and started climbing. “But promise me I can curl up in a corner and sleep the rest of the way back to the city.”

“It’d probably be best to stay on the roof,” Books called down, “so they don’t know we’ve sneaked aboard. You can sleep up there.”

“Sounds cold.”

Amaranthe secured her rifle across her back and climbed up after them without commenting, though she agreed the roof might be best. That way, they could jump off the train as it was pulling into the checkpoint, before any soldiers climbed aboard to search.

By the time she joined the men on a ledge halfway up the tower, the train was lumbering into view, its pace slow as it wound its way up the mountainside and into the pass.

“Dead ancestors with caltrops,” Amaranthe said when she spotted black-painted cars with golden imperial army logos on the sides. Those cars, dozens of them, would be filled with soldiers. More troops to support Flintcrest? Or Heroncrest? Or even Ravido? Whoever’s men they were, they wouldn’t be coming to join Sespian.

“Definitely best to stay on the roof,” Books said, “or avoid getting on altogether. How do you feel about waiting for the next train?”

Akstyr groaned, doubtlessly displeased at the idea of climbing back down, then having to climb back up again later. And then there was the cold and the limited food supply. Amaranthe flexed her numbed fingers within mittens made to ward off the chill during a quick outing into the city, not to protect digits from sub-zero mountain temperatures. Thanks to the wind, she already couldn’t feel her nose, and white crystals had frozen her lashes together. Now that they’d stopped moving, the chill was more noticeable. The sun might bring a reprieve, but another storm could come in that day too.

“We have no idea how long we’d be waiting,” she said, “and the next train might be more of the same. Someone ought to block the pass so all these reinforcements can’t continue to trickle in.”

“No,” Books said, sounding like Sicarius for a moment, he being the only one of the men who blatantly naysayed her.

Amaranthe had simply been musing aloud, so she wasn’t affronted by his vehemence. Their priority should be getting back to the city, not attacking supply lines, and she knew it. Yet… she had a hard time dropping the idea now that it’d formed.

“We don’t have any explosives,” Akstyr said. “And I’m too tired to make a landslide.”

“We wouldn’t necessarily need anything so permanent. What if we jumped on behind the locomotive, and decoupled the rest of the cars, the same as the last time we hopped a train? The soldiers would be stranded, and the railway into the city would be blocked until someone got another locomotive out to move the cars.”

Books was staring at her. “Can’t you ever take the easy route? Why can’t we catch a ride into the city and leave it at that?”

“You disagree that it’d be wise to deny reinforcements to the generals competing with Sespian for the throne?”

“No, but why do we always have to do these things?” Books sounded tired and frazzled. They’d all been up for too long without sleep.

“Who else will?” Amaranthe asked.

He growled. “Maybe we should stand back, let them all fight each other until they’re tired of it, then come in and offer a less bloodthirsty system of government to the survivors.”

“You think it would be that easy?”

Books sighed and leaned his head against the steel beam. “No.”

“It’s going to be here in a second.” Akstyr pointed at the oncoming train, the black locomotive leading the way, its grill guard like a wolf’s snarling face, full of sharp fangs.

Amaranthe shifted her weight on the ledge, readying herself to jump. “Coal car,” she instructed.

Books didn’t look pleased, but he didn’t resume the argument.

The pass was flat compared to the terrain the train had finished climbing, and it picked up speed as it bore down on the bridge. They’d have to time their jump carefully. None of them were fresh.

Judging the approach in her head, listening to the clicketyclack of the wheels rolling over rail segments, Amaranthe said, “Now!” and dropped from the tower. Wind roared in her ears, then faded as her feet hit the coal.

Elbows jostled her as she turned the landing into a roll, Akstyr and Books doing the same. They couldn’t have dropped in any closer to each other if they’d held hands. She banged someone with her rifle, and the coal scraped her fake nose off, but that was the worst of their injuries. As one, they rose into low crouches, careful to keep their heads down. If someone in the first troop car had seen them drop, or noticed them now… She was all too aware that Sicarius, Maldynado, and Basilard weren’t with her this time. As much as her ego wanted to reject the notion, she, Books, and Akstyr were the weakest fighters on the team. When she’d been separating everyone into neat parties, she hadn’t planned on combat for her half. Naive, that. She hoped Sespian was finding her men useful in Fort Urgot.

Books pointed to the locomotive and signed, Do we take it first? Or try to decouple the rest of the train?

The last time the team had decoupled cars on a moving train, Sicarius had been the one to do it. Even though she’d suggested it, the idea of attempting the maneuver herself daunted Amaranthe. She didn’t know how much physical strength it would take. At least nobody was shooting at them this time. Yet.

She eyed the route ahead. The locomotive had sped off the bridge and was on a downhill slope, picking up speed as it went. More snowy peaks loomed ahead, so there’d be more uphill swings.

Let’s wait to do that, Amaranthe signed and waved at the rest of the cars, until we slow for another climb. It’ll be less dangerous then. Besides, the engineer and fireman will be alert and ready for trouble if we try to take over after the majority of their train wanders off of its own accord.

Agreed, Books signed.

We’ll take care of those men first. She pointed at the locomotive.

Books grimaced, but didn’t argue. Akstyr yawned. Such heartening support.

On a military train, the men in the locomotive would be trained fighters, a soldier and an officer shoveling coal and working the controls. Knowing the transport was heading into trouble, its commander might have placed guards up front as well.

I’ll go left, Amaranthe signed, and you go right, Books. With luck, there’ll only be two of them, and we can stick our rifles in their backs and convince them to tie themselves up.

Akstyr, Books signed, you can usually tell how many people there are in a room. Is it just two?

Akstyr closed his eyes, winced, and shook his head. “I can’t right now, sorry.” He didn’t bother with hand signs, and Amaranthe struggled to hear him over the wind and the grinding of wheels on rails. “When I try to summon mental energy, my head hurts like there’s a knife stabbing into the backs of my eyeballs.”

Old-fashioned way then, she signed. Akstyr, you come in after me and help out if there’s more than two people, or there’s trouble.

Akstyr tossed a lump of coal. “When is there not trouble?”

The odds suggest something will go easily for us eventually. Amaranthe winked. It was more bravado than belief, but she tried to use the thought to bolster herself. Rifle in hand, she clambered down the side of the coal car, the wind tearing at the hem of her dress—ridiculous outfit to hijack a train in—and pulled her way along the ledge toward the locomotive.

On the other side, Books was doing the same. Amaranthe trusted they’d make the same progress, but paused to peer in the window next to the cab door before jumping inside. The two men in black military fatigues with engineering patches were as she’d expected, a sergeant leaning on a shovel by the furnace and a lieutenant standing behind the seat overlooking the long cylindrical boiler and the tracks beyond. What she didn’t expect were the two kids in civilian clothing. A boy and a girl, both appearing to be about fifteen years old, shared the cab with the two men. From the rear side window, Amaranthe couldn’t see much of their faces, but the girl had a pair of brown pigtails and sat in the engineer’s seat, pointing at various gauges and speaking, asking questions perhaps. The boy stood shoulder-to-shoulder with the sergeant, a book of schematics open in his hands as the fireman pointed things out inside an open panel.

“What is this?” Amaranthe muttered. “A private tutoring lesson?” She’d be less mystified if this were a civilian transport; she could imagine some warrior-caste lord on a family vacation arranging for special access for his privileged offspring, but what could children be doing on a military train? Was one of the invading generals, having realized he’d be in the capital for some time, having his family brought in? She couldn’t fathom it. Even if there wasn’t much outright fighting in the streets—or hadn’t been when she left—who would bring kids into a volatile situation?

At the other window, on the opposite side of the cabin, Books’s nose and eyes were visible, he too wearing a perplexed expression.

Amaranthe tilted her head, indicating they should go ahead with their plan. They still needed control of the locomotive. The sergeant and officer wore their standard-issue utility knives, and there were flintlock rifles mounted within reach above the cab doors, but the men were otherwise unarmed. Neither of the youths had weapons, as far as Amaranthe could tell, though in examining them, she took a closer look at their clothing and grew even more confused. Beneath parkas suitable for the cold weather, they wore homespun garments of light colors and materials, the styles foreign, though Amaranthe wasn’t worldly enough to put a finger on their origin. She only knew the children weren’t wearing the typical factory-made clothing or styles currently common around the capital.

Books was moving, so she ended her musings. A second before Amaranthe opened the cab door, the boy glanced in her direction. She hadn’t thought she’d made a noise, but she must have. Books opened his own door and jumped inside, rifle at the ready. Amaranthe entered as well, raising her firearm to her shoulder, aiming at the lieutenant’s head. The weapon wasn’t ideal in the tight space, but she had enough room. When the officer spun around, his eyes crossed as he found himself staring at the muzzle.

The sergeant’s hand twitched toward his knife, but Books prodded his arm with his own rifle, and the man scowled and desisted. The youths—siblings, Amaranthe decided, as soon as she saw their faces and the gray-blue eyes they shared—spread their arms to their sides, calmly opening their hands to show they held no weapons. That calm was surprising in people too young to have had military training, and she made a note to watch them, though the soldiers were more of an immediate threat.

“Who are you people?” the lieutenant asked, glancing out the door, as if to assure himself that yes indeed the train was still moving. Rapidly. He also shifted his stance so that he stood in front of the girl. The sergeant shifted so he stood in front of the boy, though his glances were toward the rifles above the door.

“My apologies for hopping onto your train without a boarding pass. We found ourselves lost in the mountains and need a ride to Stumps.” Amaranthe eased forward a couple of inches so Akstyr could squeeze in behind her. “Get their weapons,” she told him without taking her eyes from the soldiers.

“Hijacking an imperial train is punishable by death,” the lieutenant said, glowering as Akstyr removed his knife and patted him down for hidden items.

“Is it?” Amaranthe asked. “Then I probably shouldn’t tell you it’s not our first. Search the children for weapons, too, Akstyr.”

“Children?” the girl whispered to her brother. She had a grown woman’s curves, even if the pigtails made her look young, and Amaranthe probably could have used a different word. Indeed, the speculative consideration Akstyr gave her as he searched her suggested she was plenty old enough by his teenaged reckoning. Amaranthe was thankful his pat down was professional.

“She’s talking about you, naturally,” the brother responded.

They were speaking in Turgonian, but with a faint accent. Again, Amaranthe couldn’t place it. She wondered if Books had a better idea.

“Oh, yes,” the sister said, “I’m certain the three minutes longer you’ve had in the world than I grants you scads of wisdom and maturity.”

“Mother does say I was born with a book in my hands. I imagine that gave me a head start.”

The lieutenant exchanged glances with the sergeant, and the two men lunged, one toward Amaranthe, and one toward the door behind her. She reacted instantly, ramming the muzzle of the rifle into the officer’s sternum, the blow accurate enough to halt his charge. She tried to whip the weapon around to crack him in the head with the butt, but it caught on the doorjamb, and she settled for stomping on his instep. In the same movement, she brought her knee up to catch the soldier angling for the exit. By that point, he was stumbling for the exit, since Books had slammed the butt of his own weapon into the sergeant’s back. Amaranthe lowered her rifle, tapping the side of the lieutenant’s head with the muzzle. He’d bent over under her attack, and didn’t straighten, not with the cool kiss of metal against his temple.

“Next time, we’ll shoot.” Amaranthe hoped they wouldn’t know she was lying.

Akstyr had a knife out and was keeping an eye on the siblings, who were exchanging looks of their own. Amaranthe thought she read an oh-well-we-tried quality in their expressions. They’d been hoping to divert their attackers’ attention with their arguing? Hm.

“Slag off,” the sergeant snarled. Sort of. His cheek was smashed into the textured metal floor, and the endearment lacked clarity.

“Akstyr, tie everyone up, please. The sooner we get to phase two of our plan, the better.” Amaranthe peeked out the door toward the coal car and the rest of the train. As long as everything was attached, anyone could amble up front and cause trouble. For all she knew, shift change was three minutes away.

The girl murmured a question to her brother, not in Turgonian this time. He nodded back.

Amaranthe met Books’s eyes, sure he’d have an answer as to the language.

Kyattese, he signed.

Kyattese? Emperor’s warts, now what? It was bad enough the Nurians were tangled up in this vying for the throne—did the Kyattese want some part of it too?

Amaranthe signed, Any idea who they might be?

She was aware of the siblings watching her, noticing the finger twitches, though she was positive they wouldn’t understand Basilard’s hand code. Even his own Mangdorian people were hard pressed to follow it, given how much he’d added to the lexicon over the last year.

“I’m out of rope and belts.” Akstyr had tied the lieutenant, but not the sergeant yet. He gave Amaranthe an aggravated look.

“Get creative,” she told him.

“My head hurts too much for creativity. I—” Akstyr stood abruptly. “Sci—” He switched to code: Science.

What? Amaranthe stepped toward the siblings. She knew it wasn’t the soldiers, so that only left—was that one of those I’m-about-to-fling-magic looks of concentration on the boy’s face? Though she was reluctant to aim her rifle at a youth, Amaranthe prodded him in the chest with the barrel, hoping to distract him.

Something popped on the furnace, and black smoke poured into the cabin. Amaranthe cursed, left with little choice but to club the kid. As she drew back the rifle to swing, the girl reached into her coat, toward a pocket or perhaps a belt pouch.

“Books,” Amaranthe barked.

“I can’t—ergh.”

Someone grabbed Amaranthe from behind, yanking her away from the siblings and propelling her into the rear of the cab with jaw-cracking force. Though she threw an elbow back, trying to catch her attacker in the ribs, the person evaded the blow. Her rifle was torn from her fingers. She didn’t know if it was the same someone or someone else. Men in black uniforms moved in her peripheral vision, and soon the cabin was so crowded with bodies, she couldn’t have unpinned herself even if someone didn’t have a forearm rammed against her spine. Now it was her face that was smashed against something, her eyes meeting Books’s—he was in a mirror position two feet from her. It was neither the familiar sergeant nor the lieutenant who had him pinned, a cutlass prodding his back, but a grim-faced captain. Strong, calloused fingers tightened around the back of Amaranthe’s neck. She couldn’t see her own attacker, but he spoke from right behind her.

“Captain,” he asked in a rich baritone, that of an older but obviously not—as the grip pinning her proved—infirm man, “is hijacking a train still a capital punishment in the empire?”

“Yes, my lord. It is. In addition,” the captain said, his tone icy, “it is also quite illegal to attack warrior-caste children.”

Amaranthe blinked. It was all the movement she could manage at the moment. Warrior-caste children that muttered to each other in Kyattese? Just who in all the abandoned mines in the empire was standing behind her? Another general charging in to make a claim on the throne?

Books, with his head turned sideways toward her, must have had a better view of the man behind her, or he was simply more adept at assembling the pieces of this particular puzzle, for his mouth dropped open in… Amaranthe was sure that was recognition.

“Enlighten me,” she whispered to him.

“I… I could be mistaken,” Books whispered back, “since I’ve never met the man nor even seen him in person, military history not being my favorite subject in the least, but—”

The captain jostled Books, probably to discourage him from talking. Amaranthe wished the jostle would encourage him to get to the point.

“Who?” she mouthed, wanting the name, not an explanation.

The captain was discussing what to do with “these interlopers” with a third man, another officer. Take them to the capital to face the magistrate or simply hurl them from the train and let the mountain—and the high-speed fall—handle the matter?

“That one is a criminal with a bounty on her head.” A finger jabbed toward Amaranthe’s nose. “The others may very well be too.”

Books finally mouthed a response to Amaranthe’s question. “Fleet Admiral Starcrest.”

Amaranthe sagged insomuch as the iron grip holding her would allow.

One of the empire’s greatest war heroes. And her just outed as a criminal. Oh, yes, this was sure to go well.

* * *

The air smelled of musty tent canvas, coal smoke, and the pungent scent of sandalwood incense. That aroma was popular amongst Nurian practitioners; they believed it focused the mind. An odd odor to find in a Turgonian army tent, but not a surprising one.

Few sounds came from within the canvas enclosure—only the soft hiss of the fire—but outside, men moved about. Some spoke, some grunted and grumbled as they carried gear, and others simply walked past, their boots crunching on snow and ice.

Sicarius opened his eyes. He shouldn’t have. Wakefulness brought awareness.

And memory. And pain.

Finding the former too depressing to contemplate, he examined the latter, assessing his fitness. Though the aches that emanated from his calf, shoulder, and abdomen were not trivial, the physical pain wasn’t as intense as he would have expected. He recalled being shot multiple times, and before that, the soul construct had torn a chunk out of his leg. He grew aware of bandages around the wounds, stiff after being saturated with blood that had since dried. All of his digits responded to orders to move, and he flexed his muscles without untoward discomfort.

The mental pain…

Sicarius closed his eyes again. His son was dead. Amaranthe was dead. The rest of her team was likely dead as well—at the least Basilard and Maldynado would have fallen, just as Sespian had, crushed beneath that monstrous artifact from the past.

Footsteps crunched outside the tent. A moment later, the flap lifted, and cold air flowed inside.

A white-haired general with thick spectacles strode in, followed by two Nurians, one the silver-haired practitioner who’d created the soul construct and the other, a younger fellow with a limp. Enemies, Sicarius’s instincts cried, and he sat up, a hand going to his waist, where his black dagger usually hung. It wasn’t there. None of his knives were. He’d been stripped of shirt and shoes as well. He might have attacked the Nurians anyway, but a strange tingle throbbed at his temple. He found himself lying down on his back again, his muscles operating of their own accord—no, of the practitioner’s accord. In a final humiliation, his hands betrayed him by folding across his abdomen, fingers laced. His face tilted attentively toward the newcomers.

Flintcrest was eying him through those thick spectacles, chomping on a cigar as if he wished he were chomping on Sicarius. “It’s not a good idea, Kor Nas. Safest to kill him right now, if you can.”

“Of course I can,” the silver-haired man said smoothly, his accent barely distinguishable. “But I wouldn’t have brought my associate to continue healing his wounds if I intended to do that.”

“This man isn’t some soldier,” Flintcrest said. “He’s an ancestors-cursed assassin, a notorious one. He’s killed dozens of high-ranking Turgonians, including one of my fellow satrap governors.”

“I know precisely who he’s killed. The Nurians have also suffered at his hands. But he can be made to work for us now, as surely as my soul construct did. Perhaps one of his first tasks will be to figure out a way to retrieve my pet from the bottom of the lake.” The Nurian’s dark eyes glittered, the almond shapes narrowing further as they oozed menace toward Sicarius.

As far out into the lake as he’d hurled the creature’s trap, Sicarius would drown trying to swim down and open it. Perhaps that was a way to escape this. Better to be dead than enslaved, especially now when there was nothing to live for, nothing waiting for him if he fought and escaped. One way or another, these people would send him to his death eventually. He cared little what happened in the meantime.

“Well, get him fixed up and out of my camp,” Flintcrest said. “My men will welcome him even less than that beast of yours.”

“That is the plan, General. After which target should I send him first?”

Flintcrest grimaced. “You want me to make use of an assassin?”

“You were willing to make use of my beast, as you call it.”

“I… don’t remember agreeing to that exactly either.”

“So long as you agree to my people’s requests for favorable trade agreements,” spoke a third man as he pushed aside the tent flap and walked inside. In his early thirties, with shoulder-length black hair swept into a topknot, he wore a feathered flute and a long rek rek pipe across his back as others would wear a sword. The items were the symbols of a Nurian diplomat.

Kor Nas waved to the healer. “Finish repairing my new minion.”

“Yes, saison.”

Saison, the Nurian word didn’t mean “master” precisely, more like a term of respect for a high-ranking practitioner, often a teacher, but it might as well have meant it in this case. He’d be loyal to the older man and do as told.

“I have not forgotten, He shu,” Flintcrest told the diplomat. “The trade agreements will be created as promised.”

He shu, that was an address for a male who shared blood with a great chief, close blood usually. After all the missions Sicarius had undertaken for Emperor Raumesys, ensuring Nuria wouldn’t gain a toehold in the empire, it irked him to know that the Nurians might have found a way in anyway. He didn’t know whether they’d be worse than this Forge outfit or not. He decided he didn’t care—what could he do about it at this point anyway?—though he did admit that it bothered him that everything he had endured in his life had been for naught.

The healer laid a hand on Sicarius’s bandaged abdomen and warmth spread from the fingertips. Weariness seeped in as well. He didn’t bother seeking a meditative state, didn’t bother with trying to control his sleep—or his dreams. He simply sank into oblivion.

Chapter 2

Amaranthe, Books, and Akstyr sat against the back of the locomotive cab, their wrists tied behind them and rifles aimed at their chests. This wasn’t quite how Amaranthe had imagined the hijacking going. Judging by the scowls Books and Akstyr were shooting her, they thought the team should have remained in the coal car for the rest of the ride.

The fireman and engineer had returned to their duties, while a captain and colonel stood in a cluster with Starcrest, discussing the situation. In the confined space, one couldn’t have squeezed in any more men, so the captain had been elected to hold the rifle on the prisoners. A redundant security measure, since Amaranthe’s ankles were tied as well as her wrists, with her legs folded beneath her. She couldn’t have started a brawl if she’d tried with all her might. In addition to Starcrest and the army men, the two siblings remained in the cramped cabin; they were standing in the doorway, probably hoping their presence wouldn’t be noticed and they wouldn’t be ordered to go back to the passenger cars. The captain glanced at them a few times, as if he wished to give precisely that order, but he refocused on Starcrest and said nothing.

Amaranthe considered the legendary man, not surprised that he could command the respect of officers twenty years after his exile, but impressed. One might have expected a softness in someone who’d spent so long on the Kyatt Islands, but he appeared lean and powerful, even in his civilian clothing, a mix of browns and forest greens beneath a fur-trimmed parka. Beneath his beaver cap, his silver hair was short and thick, a regulation military cut. His height and broad shoulders surely lent him authority—he had to duck his head to keep it from bumping the ceiling of the cab—but Maldynado possessed the same physical dimensions, and people didn’t stare raptly at him, awaiting an opportunity to please—unless they were women of course. Starcrest probably had a few admirers of that sex too. His face, not so angular as Sicarius’s but of a similar vein, was weathered and creased from the sun, with an old scar bisecting one eyebrow, but he’d still fit any woman’s definition of handsome. Amaranthe could easily imagine him as a rock-solid admiral, commanding his troops in the heat of battle, though his brown eyes lacked the cold intensity she associated with so many of the senior military officers she’d met; rather, there was a hint of warmth in them, or even mischievousness, as he chatted with the men, as if now that the threat to his children had been nullified, he appreciated this break from the monotony of cross-country train travel.

So, Amaranthe mused, how do I get a legend to join our team?

Unfortunately, she feared he was heading in to join one of the other candidates, Ravido most likely, given Forge’s connection to the ancient technology and Starcrest’s history with it. Though his wife was the expert at deciphering it, wasn’t she? If the children were along, did that mean she’d come on the trip too?

After all Amaranthe had done to ensure Forge didn’t have anyone left who could control the Behemoth—she winced, remembering Retta’s horrible death—here came someone who had a better mastery of the technology than anybody else in the world.

“Lord Admiral Starcrest,” Amaranthe said during a lull in the men’s conversation, “I…” She grew uncharacteristically shy as every set of eyes in the cab swiveled toward her—even those of the engineer. Shouldn’t he be studying the snow-covered trees and bends in the tracks ahead? Amaranthe cleared her throat and pushed on. “I must apologize for any harm you perceived we meant to do to your children. We didn’t know they were up here and that they were… gifted enough to impact our, uhm, results.” Right, reminding them that she’d meant to take over the train probably wasn’t wise. She shifted to, “What the captain says about my comrades and me is true. We’re outlaws, but we’re wrongfully accused outlaws and seek to clear our names. We also seek to put the rightful emperor back on the throne, Sespian Savarsin.”

“You thought to do this by hijacking our train?” Starcrest asked, his voice mild. Deceptively so? There might have been an edge beneath it. Amaranthe had heard foreigners call the Turgonian language guttural and harsh, but his accent had been polished smooth by so many years away from the empire.

Books nudged her and whispered out of the side of his mouth, “Sespian wasn’t born yet when he was last in the empire. He might not care about him.”

“It’s not a good idea to remind your captors of their advanced age when they’re holding firearms on you,” Starcrest told him.

Amaranthe thought it had been a joke, but Books’s eyes widened with concern. “Urp?” he announced.

Akstyr snorted. He was doing his best to look tough and surly, a hard image to convey when hunched in a ball on the floor. In addition, his sneer faded every time he glanced at the girl.

Amaranthe was on the verge of deciding Starcrest’s humor might be a sign that they weren’t in as much trouble as she’d thought, but his tone grew cooler for his next question, “Why did you seek to commandeer the train?”

“It wasn’t the original plan. We were…” Amaranthe tilted her chin skyward, then caught herself—explaining a flying lifeboat that traveled hundreds of miles in minutes seemed a daunting task—and shifted her chin tilt toward the back of the train, toward the mountains they were leaving. “We were stranded in the pass and needed to get back to the city as quickly as possible—Fort Urgot was under siege, and there may be full-on war in the streets by now.”

Starcrest’s jaw tightened, and he glanced at the children. As one, they blinked innocently, clasped their hands behind their backs, and pretended to study the ceiling. Amaranthe imagined some past argument about whether they should be allowed to come or not.

“Sespian needs us,” she continued. “We’ve been helping him with—I don’t know what you’ve heard, but there’s been a business coalition trying to control him from within the Imperial Barracks for the last year, and before that, Hollowcrest was drugging him, and… well, he hasn’t had a chance yet to prove what he can do for the empire. He hired us to help him.” Technically true, though he’d only wanted to be kidnapped, and they’d succeeded at that task several weeks earlier.

“Sespian is dead,” the colonel snapped. “My lord, you can’t accept any of this woman’s words as truth. She’s a criminal, and I sincerely doubt she’s ‘wrongfully accused.’ She runs with that assassin, Sicarius, after all.”

Starcrest’s face grew closed, masked. “Does she?” he said neutrally.

Cursed ancestors, of all the times for him to hide his thoughts… He and Sicarius had met in those tunnels, twenty years earlier, she knew that, but had they been working together? Or against each other? Sicarius would have been doing the emperor’s bidding—quite loyally at that age, she imagined—and Starcrest had gone his own way afterward. Had they parted as enemies? Allies? Agreed not to kill each other this time, but with no promises for the future? She knew Sicarius respected Starcrest—one might almost say idolized, though that was a strong word to attribute to someone so cool and aloof as he. What had Starcrest thought of him?

“Where is the assassin now?” Starcrest asked.

“I haven’t seen him in a couple of days,” Amaranthe said, “but I can take you to him once we return to the city if you want to talk to him. I understand you had an adventure together once.” She raised her eyebrows, inviting him to elaborate.

He didn’t. His face grew colder.

Amaranthe couldn’t tell if that was a warning or a threat in his eyes. “He should be with Sespian right now. I know Sespian would like to see you.” Belatedly, she added, “My lord.” She wasn’t sure what his status was, as Emperor Raumesys had been the one to send him into exile and Raumesys was years dead now. The military men were “my lord”ing him, though, so she better do it too.

“If Sespian has been alive all this time,” the colonel said, “why’d he let all of this come to pass? Why isn’t he on the throne now?”

“Forge ushered him out of the city on that months-long inspection of the border forts,” Amaranthe said. “They tried to arrange his death on the train ride back, only, with the help of some plucky outlaws, he refused to die in the fiery explosion that lit up the night.” She decided not to mention that the plucky outlaws had been responsible for the explosion. The Behemoth had been on its way with plans to annihilate the train anyway.

“My lord,” the colonel said in an exasperated you’re-not-believing-any-of-this-rubbish-are-you voice.

“Let’s secure them in one of the freight cars,” Starcrest said. “I’ve kept in touch with General Ridgecrest over the years, and my understanding is that he’s currently commanding Fort Urgot.” When the colonel nodded, Starcrest finished with, “I’ll get the latest intelligence from him.”

“He doesn’t know the latest intelligence, my lord,” Amaranthe said. “He might only have the version that’s been in the newspapers. Very few know what’s really going on, that Forge has been angling to run the empire, more than the empire, from the beginning. They own Ravido Marblecrest. They—erk.”

The captain had grabbed her arm, hauling her to her feet. With her ankles bound, she had to concentrate on not tripping over Starcrest’s boots—that seemed a faux pas an exoneration-seeking outlaw should avoid—instead of speaking. Books and Akstyr were similarly hoisted. Akstyr did trip and would have planted his nose in the metal decking right in front of Starcrest’s daughter, except someone caught him by the collar, like a mother wolf picking up a pup by the scruff of its neck. This save didn’t keep Akstyr from blushing with indignation, perhaps embarrassment.

“Sergeant,” someone yelled out the doorway.

Were there reinforcements waiting in the coal car? There must be, for mere seconds passed before three burly men swung inside, crowding the already crowded cab further. Amaranthe got a face full of someone’s back, then a meaty arm wrapped around her waist, hoisting her into the air. She landed with an “oomph” on someone’s shoulder.

Her captor swung out of the cab and climbed along the narrow ledge back to the other cars. Icy wind clawed at them, and tree branches whipped past, all too close for comfort, but neither the threat of a fall nor his burden slowed him down. Amaranthe decided not to wriggle or attempt any sort of escape at that moment.

Not until she, Akstyr, and Books had been paraded through five cars of troops—more than one man hissed at her with recognition in his eyes, half-rising from a seat, a hand reaching for a dagger—and dumped in a freight car did she start considering escape plans again. Crates were piled all about them; surely she could find something to facilitate rope freeing. Although, given the overpowering smell of turnips and potatoes, that wasn’t a guarantee. The two armed soldiers stationed on either side of the door provided a further obstacle to freedom.

“Did I not say we should ride back to town and forgo the hijacking attempt?” Books asked.

Alas, the soldiers had not thought to gag anyone. Well, that could be to her advantage. Perhaps she could plant some suggestions in their captors’ minds.

“You did say that,” Amaranthe agreed. “But if we had, we wouldn’t know that Fleet Admiral Starcrest has returned to the empire, and we couldn’t have begun the process of wooing him to our side.”

One of the guards grunted with disbelief while the other rolled his eyes. Books and Akstyr’s expressions weren’t much more supportive.

“He didn’t look wooed,” Akstyr said, “and didn’t we agree to stop using that sissy word?”

“Maldynado mocked it, but we didn’t discuss removing it from our collective vocabulary.” Books dropped his head, looking much like a man who would be pinching his nose and rubbing his temples if his hands weren’t bound. “Are you suggesting that this is all going according to plan, Amaranthe?”

“No.” She made eye contact with Akstyr, silently urging him to do something to loosen their bonds. “I’m only suggesting that the plan could be modified to incorporate these new circumstances.”

“New circumstances such as us being trussed up like a leg of lamb about to go in the oven?” Books asked.

“Among other things.” Amaranthe shifted so she could gaze serenely at the door guards. “Who are you fellows working for, anyway?”

The younger of the two, a gangly private who had more growing to do, opened his mouth. The other, a corporal with a few years on him, stopped him with a glare and a, “Sh, don’t talk to them.”

“Why not? I’m sure it’s been a long, boring train ride.” Amaranthe assumed they’d come from the west coast, if they’d been toting Admiral Starcrest all the way. “We’re probably the most interesting thing to happen in weeks.”

“She’s got a point,” the private muttered. The nametag sewn onto his parka read Gettle.

“We’ll be in Stumps soon,” his comrade said. His name, Moglivakarani, must have challenged the seamstress who’d sewn the tag, shrinking the letters to fit. “Ignore them.”

“You’re not wearing any armbands,” Amaranthe observed. “Does that mean you haven’t sworn allegiance to anyone yet? You’re not working for Admiral Starcrest, are you? He’s not an officer any more, or even an imperial citizen right now, is he?”

“Not as I understand the situation,” Books said.

“We’re Colonel Fencrest’s men. That’s all that you need to know.” Moglivakarani squinted at her. “What armbands?”

A tickling sensation, like a kiss of air, brushed the hairs on Amaranthe’s wrists. Something plucked at the knot on her ropes. She struggled to keep any hint of discomfort off her face, though it was an eerie sensation, knowing her bindings were being untied without anyone being near her. “Flintcrest, Ridgecrest, and Marblecrest’s men are all wearing different color armbands on their fatigue sleeves. Someone asked Sespian if we should adopt a color for the troops he’s gathering to his side, but he objected, saying let the less legitimate parties change their uniforms. We are in the right here.” Actually, Amaranthe had said that when Yara asked, but Sespian, after hesitating over the “in the right” comment, had nodded.

“Sespian?” Moglivakarani asked.

“Emperor Sespian?” Gettle asked. “But he’s dead. That’s why all this… this.” His wave encompassed the train.

“The newspapers reported him dead, but I assure you, he’s quite alive.” Or was when she’d last seen him two days before. Or was it three now? Amaranthe needed a full night’s sleep. All the crazy events were blurring together, the days seeming unending. “My team is serving him. By detaining us, you place obstacles in front of him. He seeks to reclaim the throne even as we speak.”

The ropes fell away from her hands, and the ones on her ankles loosened as well. With her wrists behind her back, she doubted the guards could see, but she did her best to scoop the slack ropes in close anyway. Akstyr had his chin to his chest, hiding his eyes and the concentration on his face from the guards. Books gave her a slight nod. He was either free or would be shortly.

Several feet separated her from the men and the door. Since she was on her knees, with ropes tangled about her ankles, it was conceivable, no, probable, that the guards would be able to pull out their weapons before she could cross the distance and attack them. A distraction would be good.

“You could be telling us any sorts of lies,” Moglivakarani said, “thinking it’d improve your position.”

Akstyr sat up straighter, met Amaranthe’s eyes, and gave the barest hint of a nod.

“That’s true, Corporal.” She tilted her head. “I do have a letter in my pocket with his signature on it if you want to take a look. It’s dated so you’ll know it’s from this past week.”

Books gave her a curious look. She gazed blandly back at him.

“Which pocket?” Moglivakarani took a wary step toward her.

Belatedly, Amaranthe remembered she wasn’t dressed in her usual pocket-filled fatigues. Though the prosthetic nose had fallen off, she still wore her Suan costume, complete with blonde hair and a pocket-free dress. Oh, well. Improvise. The letter wasn’t real either, after all.

“It’s an inside pocket.” Amaranthe lowered her chin, eyes toward her bosom.

“I’ll get it,” Gettle blurted and hustled forward.

Moglivakarani lunged after him, grabbing his arm. “Private, you’re not going to grope the—”

Books and Akstyr leaped to their feet, each barreling into a separate man, as if they’d somehow coordinated their attack ahead of time. It didn’t take Amaranthe much longer to rise, but she needn’t have hurried. Akstyr and Books were both kneeling on the backs of their men, pinning arms behind backs and mashing faces into the worn floorboards. She gave them nods, admiring how efficient they’d grown in the last year, then collected the soldiers’ weapons.

“Perhaps I should wear dresses more often,” Amaranthe said. “That ruse doesn’t work as effectively when I’m in those figure-shrouding army fatigues.”

“Ruse?” Gettle muttered. “Does that mean there was no letter?”

“No pockets either,” Amaranthe said.

“Idiot,” Moglivakarani said.

“How was I supposed to know their hands were free? How were their hands free?”

“Tie them up, please,” Amaranthe told Books and Akstyr. She didn’t want to encourage the private’s line of thought.

The clacks of the wheels on the rails seemed to be slowing. Wondering if they were reaching the lake and the capital, Amaranthe clambered onto a crate and peered through a slat in the wall. They’d come out of the mountains, but were passing through white rolling hills rather than the farmlands west of the lake. “Willow Pond,” she guessed, naming the last stop before Stumps.

“Perhaps we should get out here and catch the next train,” Books said.

“And let a legendary war hero go without making a solid attempt to win him to our side?” Amaranthe asked.

“We did attempt that,” Akstyr said, “and we got thrown in here. We—”

The metal rollers of the sliding door squeaked, and light flooded the car. Amaranthe spun, raising her new army pistol. She halted, however, when she spotted a similar weapon already pointed at her chest. The hand holding it belonged to Starcrest. Books and Akstyr had finished tying the soldiers, and they, too, spun toward the door, crouching, fists curled into loose fists, ready for a fight.

“Interesting,” Starcrest said, taking them in, as well as the prone soldiers.

They groaned when they heard his voice, more in embarrassment than pain, Amaranthe guessed.

She lowered her pistol. Starcrest was the only one standing in the doorway as the train slowed, icicle-bedecked buildings passing behind him, but she couldn’t be certain there weren’t ten more soldiers lined up to either side of him. She didn’t want to fight with him anyway.

“We like to think so.” Amaranthe propped an elbow on a crate. “Won’t you come in? We’d love to discuss things with you.”

“That is what I had in mind.” Starcrest eyed her pistol.

Since he had the advantage anyway, his weapon still trained on her chest, Amaranthe set her firearm on the floor. If there was a chance she could earn his trust, she’d happily make the first concession. Besides, she always had Akstyr’s secret skills to draw upon if needed, so long as Starcrest didn’t bring his children in. They obviously had some mental sciences training and might sniff out Akstyr’s gift. For all she knew, they’d sensed him untying the ropes and that had been what drew Starcrest back here to start with. But, no, it must be more than that, or he’d simply have sent soldiers. If he’d come alone, he must want to talk to them about something. Maybe he’d believed what she said in the cab.

Books kicked aside the other firearm they’d taken from the fallen men. The train rolled to a stop, and Starcrest nodded and waved to someone out of Amaranthe’s sight.

That made her nervous until he holstered the pistol and stepped inside. “Mind if we let these two go?” He spread a hand toward the soldiers.

“Won’t they go off and tell that colonel that you’re in here alone, being suborned by outlaws?” Amaranthe asked.

“Suborned?” Starcrest’s eyebrows rose.

“I was going to say wooed, but I’ve been told that word is ‘sissy.’” She glanced at Akstyr.

“Well, it is,” he muttered.

“I simply wish to have a private discussion with you,” Starcrest said. “I’ve already expressed this desire to Colonel Fencrest, and he’s already expressed his vehement disapproval over the notion. What these two report back will matter little in regard to our ability to converse privately until we reach Stumps, which is, if I recall correctly, less than a half an hour away.” He stepped inside and sat on a crate. “We’ll be departing shortly, as nobody’s boarding here in Willow Pond and only two passengers have departed.”

Two fifteen-year-old siblings too young for the dangers of the capital? There was a north-south train that ran through Willow Pond, heading to numerous quiet rural towns along the way. Maybe Starcrest had relatives in the area, or his own lands might be nearby too, if he still had lands.

Amaranthe used one of the soldiers’ purloined knives to sever their bonds. Shoulders slumped, heads bowed, they shuffled for the door.

“My lord,” the corporal said, avoiding Starcrest’s eyes, “we… we were tricked. They—”

“I’m not in command of anything here, Corporal.” Starcrest said Corporal in the same tone a father might say son. “I suggest you report to your superior for orders.”

“Yes, my lord.” The corporal shambled the last two steps to the door, but paused again. “My lord, are you going to tell Sergeant Nastor… uhm.”

“I doubt I’ll have time to tell your sergeant anything before we arrive in the capital.”

“Oh.” The corporal exchanged glances with his private, who shrugged back at him. “Thank you, my lord,” he said with more spirit upon realizing that he wasn’t going to be outed for his inability to keep the prisoners secured.

They hopped from the car and jogged out of sight. A whistle blew outside.

Before the train chugged into motion again, a woman climbed up to the doorway and hesitated on the threshold until she spotted Starcrest sitting on the crate. Her thick blonde-gray hair fell in a braid down her back, spectacles framed her blue eyes, and freckles splashed cheeks that Amaranthe would consider pale, despite the tanned skin. She wore a soft gray felt dress with wool leggings and heavy boots to thwart the cold.

“Have a seat, love.” Starcrest gestured to a crate next to his. “These are the outlaws I told you about, people who have unlikely knowledge about our first adventure together.”

This must be Tikaya Komitopis, the Kyattese linguist and cryptographer. Amaranthe immediately wanted to pump her for information on the Behemoth and what she knew about Forge, specifically Suan and Retta. The sisters had both been to the Kyatt Islands on Forge’s behalf, Retta to study the ancient language, and Suan to purchase submarines for her wealthy colleagues.

“Outlaws.” Tikaya sat next to Starcrest on the crate. “And here I thought an excursion into the empire in your wake would mean a chance to meet aristocrats and military leaders from the highest echelons of society.”

“That might have happened if you’d married me when I was an upright young officer. These days… well, I don’t think anyone has scribbled out the exile mark next to my name. These—” Starcrest spread a hand toward Amaranthe, Books, and Akstyr, “—should be precisely the sorts of people you expected.”

“Should we be offended?” Akstyr muttered to Books.

“I believe so, yes,” Books said. “Word of my sublime work mustn’t have reached the Kyatt Islands yet.” He sighed.

Amaranthe swatted him on the arm.

“I haven’t been informed of their names yet,” Starcrest said, “but they know Sicarius.”

Tikaya grimaced. “Is that association as precipitous for them as it is for most people?”

Starcrest’s eyes sharpened as he regarded Amaranthe. “I don’t think so.”

“It is for us.” Akstyr pointed to his chest, then Books.

“Do you actually know what precipitous means?” Books asked him.

“Dangerous, right? You’ve used it before. You’ve even used it when talking about Sicarius.”

“I didn’t realize you’d listened.” Books sounded pleased.

“Sometimes. If I’m not doing something more important.”

Books’s eyes narrowed, some of the pleasure fading.

Amaranthe shushed them and said, “My name is Amaranthe Lokdon, and this is Akstyr and Books, formerly Professor Marl Mugdildor.”

Books’s back straightened, and he glanced at Tikaya, as if hoping she’d heard of him. She merely gazed back at the three of them with an expression of polite wariness. Outside, the train had started up, and Starcrest slid the rolling door shut before resuming a seat next to his wife. Enough light slanted through the slats in the walls that the two parties could see each other.

“You already know who I am,” Starcrest said, “but you can call me Rias. This is my wife, Professor Tikaya Komitopis.”

“Just Tikaya,” she said.

Sure, like Amaranthe was going to be on a first-name basis with people out of the history books.

Starcrest slipped a hand into his jacket and withdrew an envelope. “Do you recognize this?”

Books and Akstyr shook their heads.

Amaranthe didn’t. “Was it, by chance, postmarked from Markworth a few weeks ago?”

“It was indeed.”

“Sicarius didn’t tell me what was in it or who it was going to. I got the impression that he hoped for an answer, but didn’t expect one.”

Starcrest and Komitopis exchanged wry looks, and Amaranthe had the sense that there’d been quite a discussion as to whether to respond to that letter or not. “Can I see it?” she asked. “It doesn’t mention me, does it?”

Starcrest’s brows rose.

“I ask because there was a hasty postscript penned after I… ah, I was there when he wrote it. It’s possible my plans had some influence on the information contained within.”

“As in,” Akstyr whispered to Books, “please help, Admiral, before my crazy girlfriend blows up the empire.”

Long accustomed to their teasing, Amaranthe might not have flushed, but the topic—and the agreement implicit in Books’s smirk—made her self-conscious. “It doesn’t say that.” She eyed Starcrest. “It doesn’t, right?”

“Show her the letter, love,” Komitopis said.

The pair exchanged looks again, and this time Amaranthe couldn’t decipher the hidden meaning. For a moment, she allowed herself to wonder what it’d be like to be married to someone—not someone, Sicarius—long enough to understand each other so well that words weren’t needed. She knew Sicarius better than most, but that wasn’t saying much. It was rare for her to have a clue what was going on behind his facade.

Starcrest held out the crinkled envelope, distracting her from wistful thinking.

It was addressed in Sicarius’s precise hand to Federias Starcrest at 17 View Ridge Loop, Eastern Plantation County, Kyatt.

“We weren’t anywhere we had access to records.” Amaranthe opened the envelope and pulled out the single page inside. “I wouldn’t have guessed he knew your address.”

“Nor I,” Komitopis said. “I was alarmed to learn that.”

Starcrest spread a hand. “It’s not surprising. The emperor has surely kept track of me over the years, and he was the emperor’s man.”

“Henchman.”

Amaranthe’s lips flattened. She was glad Starcrest didn’t share his wife’s unveiled rancor toward Sicarius.

When she lowered her gaze to the page, she stared blankly at it for a moment. The words were gibberish. No, a code. Sicarius must have assumed other eyes would read any mail addressed to Starcrest from the empire. She imagined some Kyattese intelligence analyst pawing over letters to the kids from their Turgonian grandparents.

“The translation is on the back,” Komitopis said. “He used an old key, one employed during, as your people call it, the Western Sea Conflict.”

“Nothing wrong with the man’s memory then,” Amaranthe said, remembering that they’d been out in the woods when Sicarius penned the note. There were a few lines on the back, a signature, and a postscript.

“He was a bright boy,” Starcrest said. “I thought it was a shame what the emperor molded him into.”

“Oh, that’s right.” Amaranthe lowered the letter, distracted by a new thought. “You knew his father. Did you know about… more? His upbringing?” She wasn’t sure how she’d feel about the man if it turned out he had known about it and had ignored the cruelties being perpetrated in the name of creating a perfect assassin.

But Starcrest’s mouth had dropped open. “I knew his father? I wasn’t aware of Sicarius’s existence until…” His gaze skimmed over Amaranthe, Books, and Akstyr, as if he was wondering how much of those classified times he should be sharing, even at this late date. “He was fifteen when our paths first crossed.”

“According to Hollowcrest’s records, his father was… Books, what was the name?”

“Sergeant Paloic.”

Starcrest sank back on the crate, bracing himself with his palms. “I remember him. He died—”

“He committed suicide,” Amaranthe said. “After being ordered—coerced—into impregnating the woman they’d chosen to bear Sicarius. A Kyattese woman.” She glanced at Tikaya. The professor’s eyes widened, but she didn’t say anything. “According to Hollowcrest’s files,” Amaranthe continued, “Paloic’s name first came to his attention after you recommended the sergeant for a promotion.”

“I see,” Starcrest whispered. “I’d… never known.”

It was a harsh thing to bring up—it wasn’t as if Starcrest had been to blame—but she didn’t regret laying the tiles on the table. If he felt guilty, he might be more inclined to work with them. He’d already come at the behest of the letter, but that didn’t mean he meant to join forces with them. She didn’t think so anyway. Maybe she should read the translation before forming conclusions.

Lord Admiral Starcrest,

Emperor Sespian has been ousted from the throne, and numerous men with blood ties to the Savarsin line are marching armies into the city. A business coalition named Forge seeks control of the empire through a Marblecrest figurehead. Forge possesses the technology we saw on our mission twenty years ago. Among other things, they have a great flying craft from that ancient race and can use it to force their candidate onto the throne. A student of Professor Komitopis’s has mastered its flight and at least some of its many weapons. I’ve seen them. They are devastating, and the whole world is in danger. You and your wife may be the only ones who can bring about a peaceful solution. If you still care anything for the empire, you must come.

Sicarius

Postscript: Sespian is alive and in hiding, but it is unlikely anyone will be able to bring about a solution that doesn’t involve much bloodshed. The people and the military will listen to you.

Amaranthe lowered the letter and handed it to Books. Akstyr peered over his shoulder to read it as well.

“Our foremost reason for coming is to deal with the alien technology,” Starcrest said. “As for the rest… at this late date, I’m less certain than Sicarius that my influence over people or troops would be great.”

Truly? Someone had given him command of a train full of men…

“What we didn’t understand,” Starcrest said, “is why Sespian was ousted in the first place. And why he isn’t marching on the city to reclaim the throne. You say this Forge outfit has been imposing their will upon him?”

“As it turns out, Sespian isn’t Raumesys’s son,” Amaranthe said. “Forge has learned this. It’s possible the whole city will learn it soon, if it hasn’t already. We haven’t seen a paper in a couple of days.”

“Sespian is a bastard?” Professor Komitopis asked.

“Not exactly.” Given that Sicarius had personally written Starcrest and pleaded—or as close to pleading as he’d ever get—for assistance, Amaranthe didn’t think he’d mind sharing secrets. “He’s Sicarius’s son. Princess Marathi, after going through all the typical bedroom adventures one is expected to have with one’s husband, failed to produce an heir. She assumed the problem was Raumesys, and it turns out she was correct. Not wanting to suffer the fate of a previous wife who failed to produce, Marathi found someone suitable to lend his, ah, essence.”

“Essence?” Akstyr choked.

Books tried to elbow him, but they weren’t standing closely enough together.

“I didn’t think any of you Turgonian men fired blunt arrows,” Komitopis said. “You being such a hale and hearty people, prolific enough to populate a massive continent in a couple hundred years.”

Her words stirred Starcrest from whatever dark thoughts had devoured him, and he managed a half smile. “Given how many relatives you have, I don’t think you can accuse us of being overly prolific.”

“Yes, but we have a bountiful supply of sun, surf, and those fertility-boosting oysters I’ve mentioned. Your people manage it in a much harsher land, with nothing except those dreadful tooth dullers to fuel your gonads.”

Amaranthe blinked at the blunt term, but she’d heard that the Kyattese had a habit of saying things by their proper scientific names. Either that or “love apples” weren’t a common crop on the islands.

“The field rations are dreadful,” Starcrest agreed. “Or they were twenty years ago.”

“You should try one of Sicarius’s dried organ bars,” Akstyr grumbled.

Amaranthe leaned against one of the crates, eyeing the white fields passing beyond the slits in the walls. She didn’t know what to make of the professor’s derailment of the conversation. She supposed this talk of covert organizations, militant politics, and deflowered secrets was all academic to Komitopis. What did she truly care about the empire?

A banging at the door surprised Amaranthe. The train was still in motion, though the white flatlands outside had grown familiar. They had to be close to the lake, if it wasn’t already passing by on the other side of the car.

“Enter,” Starcrest called over the noise of the train.

The door slid aside, and Colonel Fencrest stood on the ledge, his face ashen. He gulped. “My lord.” He didn’t seem to notice that Amaranthe, Books, and Akstyr were no longer tied. He didn’t notice them at all.

Starcrest rose. “What is it?”

The colonel’s mouth opened and closed, but he couldn’t find words. He pointed past Amaranthe, toward the slats allowing glimpses of the countryside.

She climbed onto a crate for a better view as everyone else came to that side of the car. She leaned her temple against the cold wood, trying to see what lay ahead of the train, though she had a guess. They ought to be closing on Fort Urgot. If that army was still camped around it, that would certainly alarm someone coming into the situation new.

But it wasn’t an army that came into sight. It was…

“No,” Amaranthe whispered. Overwhelming horror swallowed her, weakening her limbs and invading her stomach like a poison. If she’d been standing, her knees would have given out, dumping her on the floor. She would have deserved it.

“Dear Akahe,” Komitopis whispered at her side.

The unmistakable black dome shape of the Behemoth towered over the landscape—what was left of it. Felled trees and flattened tents littered the white fields, along with one corner of collapsed rubble, of…

Amaranthe shook her head slowly, not believing, not wanting to believe. Never in her worst nightmares had she imagined the massive craft would crash into—onto—Fort Urgot. It had annihilated the walls, the building, everything. The people, she admitted though her mind shied away from the awfulness of that thought.

“How could we have…” Books whispered. “How could it have possibly landed in that one spot? The odds…”

Amaranthe thumped her forehead against the slats. The odds didn’t matter. What mattered were the thousands of people that had been in that fort. They couldn’t have seen it coming, not in time. They couldn’t have escaped. And if Sicarius, Sespian, Maldynado, and Basilard had still been within those walls…

Where else would they have been? She’d sent them there.

Amaranthe climbed—fell—off the crate and shambled to—she didn’t know where. A corner, she had in mind, but didn’t make it. She dropped to her knees and vomited.

* * *

Grab the rest at Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Smashwords, Kobo or Apple.

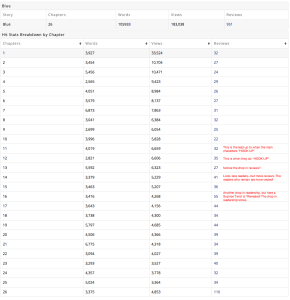

By now most people here know that Wattpad is an online community for reading and sharing stories. It has a highly active base of readers/writers and allows them to build reading lists, vote for and comment on individual chapters, “follow” their favorite authors, and interact with other reader/writers via both public and private messages. For me, Wattpad has been a wickedly fantastic way to connect with readers, sell books, and build toward that holy grail of 1,000 true fans.

By now most people here know that Wattpad is an online community for reading and sharing stories. It has a highly active base of readers/writers and allows them to build reading lists, vote for and comment on individual chapters, “follow” their favorite authors, and interact with other reader/writers via both public and private messages. For me, Wattpad has been a wickedly fantastic way to connect with readers, sell books, and build toward that holy grail of 1,000 true fans.